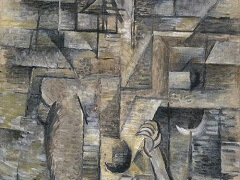

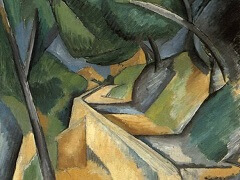

Woman with a Mandolin, 1910 by Georges Braque

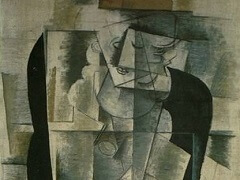

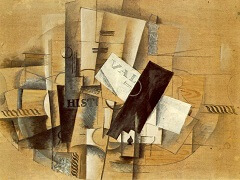

Woman with a Mandolin was painted by Braque in the spring of 1910, during the phase of analytical Cubism, the initial stage in the movement. In it the artist returns to the human figure after devoting himself exclusively to landscape and still life for two years. Perhaps this return was prompted by the impression that viewing twenty-four of Camille Corot's paintings at the Salon d'Automne of 1909 made on him. Corot showed him how the addition of a musical instrument infuses the person portrayed with the calm of a still life, and the allegorical and expressive possibilities of the theme were coupled with Braque's great passion for music. Corot's seated women in melancholic poses holding musical instruments impressed both Braque and Picasso, whose works display their mark. Both artists were quick to respond to the stimuli of the nineteenth-century master and during the first months of 1910 Braque made several experimental drawings and painted the present rectangular Woman with a Mandolin in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza and another in an oval shape, the first Cubist painting to be executed in that format. Around the same time Picasso produced an oval Woman with a Mandolin and a rectangular Woman with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier). As some art historian points out, with these two oval paintings on canvas, the oval format - typical of eighteenth-century decorative painting - made its full appearance in Cubism.

Like the still-life objects Braque had painted the previous year, the figure in Woman with a Mandolin breaks down into its different components, which are joined together again in a new arrangement. In this phase of the fragmentation of form, the artist employs a narrow range of ochres , greys and browns. Despite this reduced palette, Braque achieves many painterly effects using a Divisionist technique of small brushstrokes and a very loose and luminous facture. Background and figure fuse into a web of vertical and horizontal lines, into a spatial continuum composed of small, interpenetrating planes. Some fragments are recognizable , such as the mandolin and the hand that holds it, while others, such as the head and shoulders, are so well integrated into the abstract space of the background plane that they are barely discernible.